16 Tips for Writing AI-Ready C# Code

How to make it easy for AI agents to work with your .NET codebase

This article is my entry as part of C# Advent 2025. Visit CSAdvent.Christmas for more articles in the series by other authors.

Over the past year, I’ve been using an increasing amount of AI assistance across various tools to write and refine C# codebases. I wanted to distill some of the key takeaways from that development as well as insights gleaned from several AI workshops I led this week with Leading EDJE into an article to help you write and maintain C# codebases that are optimized for AI agents.

In this article we’ll walk through 16 of my current best practices for building C# codebases that are as easy as possible to use from AI tools like Copilot, Cursor, or Claude Code. These tips will be broken down from the more foundational concepts that could apply to any language to structural patterns relevant to C# applications to very specific C# language and library capabilities that help decrease the amount of time AI agents spend churning while trying to generate solutions.

Editing note: don’t worry; I’m not turning into one of those clickbait list people. I came up with my list of points while outlining this article, discovered I had 14 and found an excuse for a 15th while writing it, then found an additional one during final edits. I remain committed to quality content authored by human hands (with a little AI assistance thrown in for editing)

Foundational

Let’s start by discussing some foundational ways of improving your experience working with AI agents in .NET codebases at a high-level, regardless of which AI tooling you’re using.

Tuning behavior through Agents.md

A common standard for AI tooling is to use an Agents.md file located in the root of your repository. This file should contain common instructions that the AI agent should receive for any request you might make of the agent.

A sample Agents.md file might start something like this:

You are a senior .NET developer and designer skilled in writing reliable, testable C# code to solve a variety of problems in a modern production system. Your code should be easy to understand and easy to test. You are competent in a variety of libraries and languages and follow established .NET best practices.

If you’re not comfortable with writing your own Agents.md file, I recommend looking at community curated ones on Cursor.Directory or searching for an Agents.md file you like on GitHub (provided its repository’s license meets your needs).

The role of your Agents.md file is to set the stage for good interactions with your agent for a variety of common tasks. The agents file is one that you’ll likely want to reuse between different repositories so it shouldn’t contain customizations for your specific project - that’s something that more suitably belongs in a README.md file or in custom context rules as we’ll discuss later.

Documenting common operations in your README.md

Many AI agents will look at your README.md file when getting oriented on your code. README.md files often contain common context on what your codebase represents as well as standard practices for configuring, building, deploying, and testing your application.

I strongly recommend that your README.md file include a brief section on building and testing your application, for example:

This application relies on .NET 10 and can be built using

dotnet build. Unit tests can be run viadotnet testand are important to run all tests in the solution in this way before considering any change complete.

While this may seem trivial and common sense, I’ve seen enough instances where models will not attempt to build the code, will use incorrect syntax, or - more frequently - will omit running tests or will not run ALL tests - just ones related to their specific change.

One practice you may want to consider with your README.md file is to keep it as small and focused as possible and to have it link to additional markdown files in the repository as needed. For example, if new developers need to install and configure a number of dependencies when setting up the repository, that’s important information to document, but it’s going to be extra noise to your AI agent because they’ll be operating in a pre-configured environment (either your local machine or a cloud agent configured via dockerfile). Take these extra configuration steps and put them into a GettingStarted.md file, then link to this file from your README.md.

You can do the same practice with larger pieces of content as well, such as detailed architecture or database schema information. By including links to the content in your README.md you keep your file small and focused while enabling the AI agent to discover and search those files if it feels their contents could be relevant to the tasks they’re trying to achieve.

Warnings, Analyzers, and Errors

Compiler warnings are not “pieces of flair” for your codebase. Rather, your compiler warnings should indicate that something is potentially wrong with something in your codebase and should be addressed.

What I’ve found is that if I have a codebase with many pre-existing warnings, AI agents will do what developers do and ignore warnings on existing code, missing any warnings introduced by their changes as well.

When warnings are addressed (which AI can help with), your AI agents are more likely to pay attention to them, but not guaranteed to do so. If you absolutely want your AI agents to pay attention to warnings, you can always modify your projects to treat C# warnings as compiler errors, but you’ll need to get to 0 warnings for the project in order to do so, and this may make developers on your team less productive and more grumpy in the short term. You can always omit certain warnings as well. See the Microsoft documentation for more details on the various compiler options for handling all or specific warnings as errors and muting warnings your team doesn’t care about.

You can augment this further by adding in additional code analyzers that will identify additional potential issues and standards deviations in your codebase, helping AI self-govern and your team identify and correct it when AI fails to do so itself. Some analyzers you might consider include:

- Microsoft.CodeAnalysis.NetAnalyzers standard .NET Analyzers

- StyleCop.Analyzers the old StyleCop analyzers ported over to the new Roslyn compiler platform

- Meziantou.Analyzer additional good practice analyzers

Depending on the libraries your team works with there may be some additional analyzers to consider and include as well.

Formatting AI code

Some AI models and tools generate code that is oddly formatted and does not match the rest of your codebase. These code files might have no indentation whatsoever or deviate from your team’s standards for curly brace placement or other common practices you’ve adopted. This can make AI generated code feel even more alien in your codebase.

You can combat this using formatting tools baked into your IDEs or through standardized commands such as dotnet format.

You can even set a pre-commit hook in git to run dotnet format before a commit is created, or as part of the build by making a custom step in Directory.build.targets as shown here:

<Project>

<!--

Auto-formatting during build.

Set EnableAutoFormat=false to disable auto-formatting (e.g., in CI/CD pipelines where formatting is checked separately).

-->

<PropertyGroup>

<EnableAutoFormat Condition="'$(EnableAutoFormat)' == ''">true</EnableAutoFormat>

<_FormatLockFile>$(MSBuildThisFileDirectory).formatting.lock</_FormatLockFile>

</PropertyGroup>

<!--

Format code before compilation at the solution level.

This ensures all code is consistently formatted according to .editorconfig rules.

Uses a lock file to ensure formatting only runs once per build session.

-->

<Target Name="FormatCode"

BeforeTargets="Build"

Condition="'$(EnableAutoFormat)' != 'false' AND !Exists('$(_FormatLockFile)')">

<Touch Files="$(_FormatLockFile)" AlwaysCreate="true" />

<Message Text="Formatting C# code files in solution..." Importance="normal" />

<Exec Command="dotnet format --include-generated --verbosity minimal --no-restore"

WorkingDirectory="$(MSBuildThisFileDirectory)"

ContinueOnError="true"

IgnoreExitCode="true" />

</Target>

<!--

Clean up the lock file after build completes.

This ensures formatting can run again in the next build.

-->

<Target Name="CleanupFormatLock"

AfterTargets="AfterBuild"

Condition="Exists('$(_FormatLockFile)')">

<Delete Files="$(_FormatLockFile)" ContinueOnError="true" />

</Target>

</Project>

Note: if you follow this example, make sure the lock file is ignored in your .gitignore file.

By taking a proactive approach and ensuring that you either manually format your code using tools or have code auto-formatted on build or commit, you ensure that the code in your solution meets your team’s standards - even when an AI team member writes it.

Structural patterns for AI assisted C# development

Now that we’ve covered some of the broader and more generic foundational aspects of AI assisted development, let’s dive into the realm of .NET code by talking about broader patterns in C# code that can help AI agents across your codebase.

Global using statements as a safety net for AI agents

One problem I often encounter with AI agents is that they generate code that is correct but fails to bring in the using statements to support it. Agents will either miss this entirely or spend cycles (and tokens) running builds and trying to identify and resolve the issue. You can circumvent this in many cases by adding a C# file that contains your global using statements.

This file is often named GlobalUsings.cs and is typically placed in a project’s root directory and contains entries like this:

global using System.Diagnostics;

global using System.Diagnostics.Metrics;

global using System.Text;

global using System.Text.Json;

global using Microsoft.Agents.AI;

global using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore;

global using Microsoft.Extensions.AI;

global using Microsoft.Extensions.Logging;

Because you’ve centralized using statements into a single shared location within each project, AI agents no longer need to worry about including using statements when bringing capabilities into each file. Sometimes your AI agents will need to add namespaces that are not yet part of your global using statements, but that’s a less frequent occurrence than the case I observe where a using statement you already employ elsewhere in your code is now needed in a different file.

One caution here: namespaces exist for a reason, and the more namespaces you include in your GlobalUsings.cs file, the greater the chance that you’ll bump into new compiler errors due to types sharing the same name but living in different namespaces. In these cases you (or your AI agents) will need to disambiguate between the two and perhaps specify that decision through a using statement as well.

Directory-based package management

On a related note, if your solution has many projects that all rely on similar NuGet packages, you may benefit from centralized package version management in a Directory.Packages.props file.

These files allow you to specify the version of a dependency in a single file and free up your individual projects to simply state that they depend on this dependency without having to specify which version of it they depend on.

Here’s a snippet from a Directory.Packages.props file for reference:

<Project>

<PropertyGroup>

<ManagePackageVersionsCentrally>true</ManagePackageVersionsCentrally>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageVersion Include="Aspire.Hosting" Version="13.0.2" />

<PackageVersion Include="Aspire.Hosting.Azure" Version="13.0.2" />

<PackageVersion Include="Aspire.Hosting.PostgreSQL" Version="13.0.2" />

<PackageVersion Include="Aspire.Hosting.AppHost" Version="13.0.2" />

<PackageVersion Include="Aspire.Hosting.Testing" Version="13.0.2" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

Centralizing package management prevents issues that could arise from one project relying on an old version of a dependency and then an AI agent adding a NuGet reference to a different version of that package, resulting in inconsistencies and version mismatches throughout your project.

If you do find yourself moving to centralized package management, I do strongly recommend you define a NuGet.config file for your solution as well, like the following one:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<configuration>

<packageSources>

<clear />

<add key="nuget.org" value="https://api.nuget.org/v3/index.json" protocolVersion="3" />

</packageSources>

</configuration>

By explicitly declaring the package source your project depends on, you eliminate potential issues running your code on machines that have more than one package source installed on them.

Standardized dependency injection discovery with Scrutor

If I had a nickel for every time AI created a new service and interface definition and then failed to register that service correctly for dependency injection somewhere, I’d have a lot of nickels.

While you can try to mitigate AI making these mistakes via integration tests or specialized prompts, I’ve found an easier path is often to use convention-based service discovery via a library like Scrutor.

Scrutor lets you define rules for discovering and registering services in a service collection and how those services are registered and defined.

Here’s a sample Scrutor invocation from a project I’m working on at the moment:

services.Scan(scan => scan

.FromAssemblyOf<GameService>()

.AddClasses(classes => classes.InNamespaceOf<GameService>())

.AsSelfWithInterfaces()

.WithScopedLifetime());

This code finds all classes in a specific services namespace and then registers those classes as scoped instances in the dependency injection container. This example does this not just for the class themselves but for all the interfaces each service implements.

The net result of this relatively straightforward block of code is that if I come along and add a new interface and new service class in a standardized area I’ve configured Scrutor to look at, Scrutor will pick up the new definitions without requiring any additional dependency injection configuration. This means that AI (and our developers) can just focus on following established patterns and don’t need to worry about forgetting DI registration on their new services.

Prefer single-file components

One thing I’ve noticed about AI tooling is that it doesn’t always pull in all the files relevant to a task unless I’ve specifically mentioned them or referenced their existence.

For example, an AI agent may understand that my Blazor components have .razor files, but it may not think of checking the related .razor.cs or .razor.css files for logic or styling. However, if I instead keep all of my logic in the same .razor file, AI agents will look through that full file when they pull in the file for analysis or modification and will be more likely to update the relevant code behind or styling related to the visual layout.

Depending on how much you find AI struggling with your files and components, it may be worth moving away from these separate files and more towards single-file components which can be easier for AI agents to ingest and process. Of course, doing so also increases the size of those files and increases the amount of context heading the agent’s way, which is not always a good thing. However, if you do have files that are simply growing too large, this could be a good motivator to pull logic out into other components or into shared helper methods elsewhere.

Providing additional context for specific areas of your code

Some AI tools such as Cursor allow you to define additional context for specific areas of your code, whether that’s directories, file types, or wildcard pattern matching.

While different tools have different ways of doing this and different levels of capabilities, I’ve found that this capability is very helpful for providing additional instructions that are only relevant for certain areas of code.

For example, you might use your AI toolset to define additional context for things like:

- Directing tests to use the Arrange / Act / Assert pattern, Shouldly for assertions, and use InlineData where possible to combine different tests into the same test method.

- Defining patterns and anti-patterns for things like Entity Framework - as well as reinforcing commands for common operations like adding new migrations.

- Detailing your requirements for documentation, error handling, authentication, rate limiting, and paths on controller endpoints.

To help illustrate this concept, here’s a sample Cursor rule that gets applied to any .razor file:

---

globs: *.razor

alwaysApply: false

---

Pages that have interactive components must include a @rendermode InteractiveAuto directive.

Using this rule we can add in an extra piece of context only when it is likely to be needed (when working with .razor files) and otherwise omit it, keeping our agents focused on only the most relevant context.

While different tools have different capabilities, syntax, and approaches, I am overall very excited about the ability to gain additional control over our AI agents working in our codebases.

C# language features

In this final section we’ll look at some C# language features that make things easier for AI to get right - or easier for them to discover mistakes they’ve made in early attempts.

Prefer the var keyword

If you’ve ever worked with me or read some of my prior articles or books, you may have noticed how I tend to avoid the var keyword in C# and instead favor the C# target-typed new syntax with lines like this:

GameBuilder builder = new();

Or, when working with a method result:

GameBuilder builder = GameFactory.CreateBuilder();

While I think this is great for human readability, I’ve noticed that AI agents struggle more when having to specify the exact type name for something - particularly when multiple generic type parameters are involved. This relates somewhat to the point on using statements earlier in that one of the common issues they introduce is failing to add the right using statement for the type they reference.

By using var instead of using the exact type name, it makes it easier for your AI agents to generate compliant code and make structural changes in a codebase, since the logic is simplified down to lines like the following:

var builder = GameFactory.CreateBuilder();

I personally do not like this style because it obscures the type of object being created. While most IDEs will show you the inferred type as a tooltip or as an extra label on the editor surface, this is not yet present in most code review or diffing tools, meaning this type context - including possible nullability - is potentially lost during code review.

All the same, in my observation, var is more efficient for AI agents making changes to code, so it’s up to you and your team to determine if you optimize for human readability in code review or in terms of development or maintenance time productivity.

Required keyword and nullability analysis

In C# you can define properties as required using syntax like this:

public required string Name {get; init;}

This line of code states that the object in question has a Name property that is a string, that string is non-nullable (otherwise it’d be a string?), the value can only be set during object initialization (init keyword), and that it is not legal to instantiate the object in question without providing the Name property (the required keyword).

While I’ve been defining more and more objects with immutable required properties like these anyway from a quality perspective, I’ve noticed that the C# compiler’s enforcement of the required keyword is really helpful for AI systems, as they’ll try to instantiate objects without fully populating their properties (even if the agent created the property to begin with), but the presence of a compiler error related to the property helps anchor the agent towards working solutions and prevents certain types of defects from even being possible.

While you don’t need to use init-only properties or nullability analysis to take advantage of the required keyword, I’ve found myself generally happier and more productive when working with immutable objects than I am when I work with objects that may slowly mutate into bad states over time if not carefully controlled.

Nowadays nullability analysis should be your default for new projects and you should be working to bring older .NET solutions into compliance with analysis bit by bit over time, because the ability to know if something may be null can save you from writing tedious boilerplate code in many places and help prevent critical exceptions in others.

Using the with keyword for modifying records

The with keyword is fantastic when working with record types because it lets you quickly clone an object with slightly different characteristics without needing to fully represent the properties of that object at the time of instantiation.

For example, the following code represents a new Point that is located near the original Point, but at a slightly different X position:

Point newPos = originalPos with { X = originalPos.X + 1 };

This syntax helps focus us on what’s changed about an object and it minimizes the amount of information about the object an AI agent needs to worry about.

For places where record types are not viable, you may be able to get similar mileage via dedicated constructors or factory methods, but I’ve not done as much work in this area.

Mapping with Mapperly

One thing I have done work with is using libraries like Mapperly to build boilerplate translation code to copy properties from entity objects into DTOs (and vice versa) in a minimal and efficient manner.

For example, if I had a Player entity defined like this:

public class Player

{

public required string Id { get; set; }

public required string RulesetId { get; set; }

public string? Description { get; set; }

public required string Name { get; set; }

public Ruleset? Ruleset { get; set; }

public ICollection<Game> Games { get; set; } = new List<Game>();

}

And a PlayerDto object defined as follows:

public class PlayerDto

{

public required string Id { get; init; }

public required string RulesetId { get; init; }

public string? Description { get; init; }

public required string Name { get; init; }

}

I could write a PlayerMapper using Mapperly like this:

[Mapper]

public static partial class PlayerMapper

{

[MapperIgnoreSource(nameof(Player.Ruleset))]

[MapperIgnoreSource(nameof(Player.Games))]

public static partial PlayerDto ToDto(this Player player);

public static partial PlayerDto[] ToDto(this IEnumerable<Player> players);

}

Mapperly will then automatically match properties between the two objects and generate reflection-free code that copies from one object to another in an efficient manner.

The net result of this is that when an AI agent needs to modify an entity, there’s a good chance that the code to map from the entity to a DTO will be generated automatically by Mapperly. In cases where the AI agent makes a modification to one object but not the other (or the property names don’t match) Mapperly will generate build warnings that will help alert you and the AI agent to this and let you quickly resolve the issue, guiding your code in the right direction.

Preferring manual mocks over mocking frameworks

One area where I’ve seen AI agents struggle significantly is with complicated setup logic for mocking libraries like Moq. In these libraries, the agents generate what looks like valid mocking code and the code even compiles, but in reality the code will frequently encounter issues where it’s setting up for something slightly different than what’s actually happening or key parameters are ignored or misplaced, resulting in test-time failures.

I’m currently searching for a better answer to this problem or better libraries that are easier for AI to work with, but at the moment I’m wondering if it’s more efficient and maintainable for AI to manually create the test doubles than to get them to work correctly with mocking libraries without strong compile-time error detection.

One of the significant reasons for using a mocking framework to begin with was saving developer time in creating and maintaining mock objects. In today’s AI-powered world, this may no longer be relevant and it might be worth revisiting our assumptions and seeing if guiding AI towards creating and maintaining mock objects results in cleaner tests that AI struggles less with.

If you have thoughts on this topic or alternative solutions, I’d love to hear from you, but this is where I am currently leaning at the moment.

Naming considerations

The final tip I want to touch on is that what you name things matters. A variable named approvedEmailAddresses is more clearly understood than a variable named approvedList or simply approved. Even if the context of something is obvious to a human, an AI may struggle with things. I’m not saying that we start requiring our variable names be six words long, but I do think that what we name things should provide context into what they actually represent in order to save ourselves from costly mistakes stemming from AI misunderstanding business logic.

Of course, you can insulate yourself from this a little by including comments in your methods detailing the high-level business logic. For example, the following comments help provide additional context to the AI agent and can prevent misunderstandings of code:

// In testing and UAT environments we have a set of allowed email addresses we're allowed to contact.

// If the list has at least one address, we need to ensure we're only sending to approved addresses to avoid spamming users during testing.

The other nice thing this type of comment does is that it helps the code show up in AI searches against indexed data in editors like Cursor that generate embeddings for each file in your solution and can help the AI agent find relevant code faster.

Of course, this only helps if your comments are accurate and reflect the ground truth of what your methods actually do.

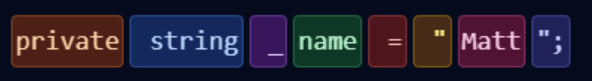

Variable names and tokenization

The final thing I want to state in this section is that I am starting to reflect on old habits of mine around naming fields and other private class-level data using an underscore prefix. While this practice has been helpful to me as a developer for many decades, I feel its time may be at an end - both in terms of usefulness as our tools evolve and in terms of the potential cost of it.

To illustrate what I mean, let’s look at two different variable declarations in the lovely token visualizer at https://santoshkanumuri.github.io/token-visualizer/.

The first one uses my previously preferred underscore prefix for private fields:

As you can see, the tokenizer assigned a unique token for the underscore character and separated that from the rest of the variable name.

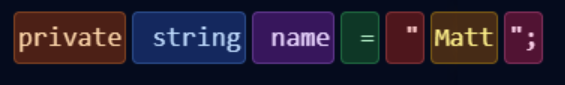

If I had used a more modern scheme and omitted the underscore, that token would be gone and the result would be:

Each tokenizer operates differently, but by reducing legacy junk prefixes and suffixes that no longer deliver sufficient value, we can actually help optimize our systems slightly by reducing the volume of tokens required for the same code.

I’ve not done any dedicated experimentation on the long-term effect of this on cost or on accuracy improvements, but I believe that every little bit matters and I’m no longer convinced that my oldschool-style prefixes are contributing development value to humans versus the slight optimizations I can see from potentially removing them.

If you’ve done any research in this area or know of any, please let me know as I’d be eager to see it.

Conclusions

While 16 tips seems like a significant amount, I feel like this article is just scratching the surface on the topic of improving our codebases to make them more easily digestible to AI systems. While this might not matter to you initially, making it easier to work with AI in our codebases can result in less human frustration, faster and cheaper iteration cycles, and greater degrees of success adopting AI productivity tools.

However, the real struggle comes from reviewing and testing the output of such systems in ways that minimize risk to production systems, and that struggle is perhaps central to what lies ahead for us as developers.

While I have more to say on that particular topic, our time is at an end for this article, so I would encourage you to identify the tips that resonate the most with you, look at the tooling that you currently use and the different ways you can inject additional context into it, and consider the things AI systems are currently struggling the most with in your codebase. Once you’ve figured that out, then look for the tips and tricks that best help improve that experience.

For now, goodbye and happy coding in this strange new world we’ve found ourselves in.